History

history

Characters

Torre del Greco has been the scene of significant events involving important figures who, for religious, institutional or cultural merits, have brought prestige to the city and its history.

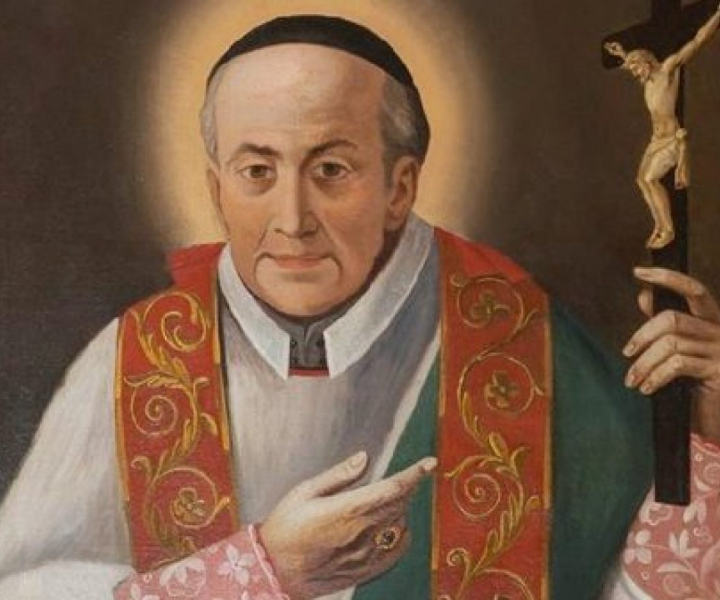

San Vincenzo Romano

Don Vincenzo Romano, proclaimed a saint by Pope Francis in 2018, was born and lived in Torre del Greco. During his ministry, which lasted 33 years, he devoted himself above all to his fellow citizens, as well as helping them in their daily tasks (political, social, etc.), through evangelising peasants in rural chapels and then as Spiritual Father of the Congregation of the Assumption. He took care of the education of the young, the care of the sick, the assistance of the needy, and even tracking down the hideouts of criminals. Thanks to his unceasing and tireless work on behalf of the poor, the sick, seafarers and the needy of all kinds, he earned the nickname 'Prevete faticatore' (in Neapolitan, 'the working priest') from the local population. The terrible eruption of Vesuvius on 15 June 1794 almost completely destroyed the town and its parish church, of which he had meanwhile been appointed assistant parish priest. In 1799, on the death of the parish priest, 'Don Vicienzo' (so affectionately called by the people) became the provost curate of the parish and completed the reconstruction work, making it larger and more majestic. He died on 20 December 1831, due to illness. His liturgical memory is celebrated on 20 December, although in Torre del Greco he is celebrated on 29 November, by tradition.

Giacomo Leopardi

Giacomo Leopardi is considered the greatest poet of 19th century Italy and one of the most important figures in world literature. During the years he spent in Naples, he devoted himself to writing his Pensieri, which he probably collected between 1831 and 1835, resuming many notes he had already written in old works he had interrupted with the help of his friend Ranieri, until the last days of his life. The last octaves would have been dictated by the dying Leopardi shortly after finishing his last poem, Il tramonto della luna. Some doubt may arise if one considers that Ranieri invested money after the poet's death to have them published as authentic, with little financial success. In 1836, when the cholera epidemic broke out in Naples, Leopardi went with Ranieri and the latter's sister, Paolina, to the Villa Ferrigni in Torre del Greco, where he stayed from the summer of that year to February 1837 and where he wrote 'La ginestra o il fiore del deserto'. It was in Campania that he composed his last Canti La ginestra o il fiore del deserto (his poetic testament, in which we can see the invocation to a fraternal solidarity against the oppression of nature) and Il tramonto della luna (completed only a few hours before his death). The poet's stay in the Villa torrese, in the Santa Maria la Bruna area, which was the source of inspiration for his last poems, meant that the city could boast the title of Leopardi City.

Sir William Hamilton

Sir William Douglas Hamilton (Henley-on-Thames, 13 December 1730 -London, 6 April 1803) was a British diplomat, archaeologist, antiquarian and volcanologist. An English ambassador to the court of Naples from 1764 to 1800, he was widowed on 25 August 1782. During this period he studied volcanic activity and earthquakes, wrote a book on Pompeii, bought the rich museum of Count Francesco Grassi of Pianura and amassed a remarkable collection of ancient vases, part of which was transferred to the British Museum in 1772. Sir William Hamilton arrived in Naples in 1764 as 'envoy extraordinaire' of George III, King of England, and remained there until the end of the century. In 1767 he rented, for 800 ducats a year, part of the Sessa palace, from which he could admire the spectacular panorama of the gulf and Vesuvius. In 1768, Sir William Hamilton was appointed a corresponding member of the Royal Society. In a short time, he had become an expert in volcanology, thanks in part to the studies he conducted on the slopes of the volcano from his Casino in Torre del Greco (although he referred to it in his correspondence as Portici), where he preferred to spend his time and receive guests. To Sir Hamilton, we owe many archaeological finds and furnishings exhibited at the British Museum in London.

Francesco Solimena

Francesco Solimena, known as l'Abate Ciccio (Canale di Serino, 4 October 1657 - Barra, 5 April 1747), was an Italian painter and architect. Active in the Neapolitan area, albeit with commissions from major European courts, he is considered one of the artists who best embodied late Baroque culture in Italy. He worked for the major European courts, although he hardly ever moved from Naples. He died in his villa in Barra on 5 April 1747, and his remains are preserved inside the church of San Domenico. Several dozen pupils were trained in his workshop. The City of Naples, the district of Barra, and the Dominican fathers, on the 250th anniversary of his death, placed a plaque on his tomb inside the Church of San Domenico. In Torre del Greco he had a villa along the Royal Road of Calabrie, donated by King Charles.

Enrico De Nicola

Enrico De Nicola (Naples, 9 November 1877 - Torre del Greco, 1 October 1959) was an Italian politician and lawyer, the first President of the Italian Republic. He was elected Provisional Head of State by the Constituent Assembly on 28 June 1946 and held this office from 1 July of the same year to 31 December 1947. On 1 January 1948, in accordance with the First Transitional and Final Provision of the Constitution of the Italian Republic, he exercised the powers and assumed the title of First President of the Italian Republic, retaining them until the following 12 May. As President of the Italian Republic, he only gave the office to one Prime Minister, Alcide De Gasperi. De Nicola also held numerous other public offices: in particular, he is the only one to have held both the office of President of the Senate of the Republic and that of President of the Chamber of Deputies. In his lifetime, he was also the first president of the Constitutional Court, thus holding four of the five highest offices in the state.

Historical Events

A journey through the history of Torre del Greco to retrace the most salient events, such as the devastating eruptions of Vesuvius, that helped transform the face of the city, sometimes radically.

79 d.C.

In Roman times, as numerous archaeological finds testify, Torre del Greco was probably a residential suburb of Herculaneum. Numerous aristocratic villas and baths had already sprung up here at the time, enjoying the tranquillity of the area and its central position within the Gulf of Naples. Just as it happened with the neighbouring urban centres, the devastating eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D. also devastated these places and the Domus present, to the point of reshaping the entire ground and repelling the sea for over 500 metres. The city's history is intertwined with that of the subsequent eruptions of Vesuvius, among which the eruptions of 203 and 472 were notable, from which the inhabitants fled and then returned to rebuild their homes. It was during these troubled centuries that the villages of Sola and Calistum (Villa Sora and Calastro) sprang up. Their names survive in two of the districts, both facing the sea, whose inhabitants obviously carried out purely seafaring activities. From the union of the two inhabited nuclei of Sola and Calastro, the Casale di Torre Ottava (Turris Octava) was formed in the Middle Ages. So called because it was 8 miles from Naples, it also retained its present name from 1324 onwards in memory of some eminent personality of Greek origin who lived in the area.

1631

In 1631, an eruption of massive proportions destroyed the entire sea-facing slope of Vesuvius, and the city of Torre del Greco was hit by muddy torrents and huge lava flows, one of which in particular generated the Scala cliffs (near Calastro). With the death of Nicola Guzman-Carafa, son of the Viceregina of Naples Anna Carafa, also formerly Useful Mistress of Torre, in 1689, the rule of the Carafa family came to an end.

1699

On 18 May 1699, the Redemption of Torre del Greco took place. With the Redemption came the legal configuration of the 'Baron' as the holder of the University's assets and their representative at the Royal Court, as provided for by the laws in force. The first Torrese Baron was Giovanni Langella, an honest and very poor man, who expressly renounced all economic claims for this appointment at the time of the investiture. His family retained the barony until 1806 when, with the advent of Joseph Bonaparte, feudalism was abolished. Between the 17th and 18th centuries, in the Bourbon era, as in Roman times, several stately villas were built in the Vesuvian area: the villas of the Golden Mile, which preserve splendid examples of 18th-century architecture. In 1707, the city suffered the heavy fall of pyroclasts from Vesuvius, along with the municipalities of Scafati, Striano and Boscotrecase, with damage to crops and hundreds injured.

1794

The subsequent violent eruption of Vesuvius, on 15 June 1794, buried the historic centre under a thickness of lava of around 10 metres, destroying much of the city. The sturdy bell tower of the parish church of S. Croce, which was later rebuilt on top of the one submerged by the igneous lava by the recently sanctified Don Vincenzo Romano, stood firm. The numerous eruptions of Vesuvius, which had caused extensive damage to the city over the centuries, led to the choice of the municipal coat of arms, which includes a tower, on which the motto of the phoenix is inscribed: ?Post fata resurgo?. The city became a municipality under the rule of Joseph Bonaparte in 1809, with the election of its first mayor, Giovanni Scognamiglio.

1861

It is said that from 8 December 1861, until 31 December, a terrifying eruption of Vesuvius of the effusive-explosive type and a violent earthquake devastated the city of Torre del Greco. The city was then hit again by another eruption: lava and strong earthquakes swept through the area, causing much damage to monuments and homes.